Shein is a popular online destination for social influencers and shoppers to stock up on stylish yet affordable clothing, but a new complaint argues that the firm maintains its edge by participating in “egregious” copyright theft that constitutes racketeering.

The complaint was filed on Tuesday in California federal court on behalf of three designers who said they were “surprised” and “outraged” to see their designs faithfully replicated and sold by the Chinese fast-fashion shop.

The copied products weren’t “close call” replicas, where designs are interpreted with certain liberties, but were “truly exact copies of copyrightable graphic design” that were sold by Shein, the lawsuit argues. The corporation reportedly engaged in a pattern of copyright infringement as part of its drive to manufacture 6,000 new things each day for its millions of customers. That amounts to a violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, the claim contends.

“Shein has grown rich by committing individual infringements over and over again, as part of a long and continuous pattern of racketeering, which shows no sign of abating,” the suit argues.

Shein is the largest apparel store in the world with annual sales of approximately $30 billion, more than H&M and Zara combined, the lawsuit argues.

A corporate spokeswoman told CBS MoneyWatch it doesn’t comment on pending cases.

The lawsuit is just the latest in a series of issues Shein has faced. In May a bipartisan group of two dozen legislators asked the Securities and Exchange Commission to put the brakes on an initial public offering by Shein unless it verified that company did not use forced labor from the country’s largely Muslim Uyghur community.

“Downright evil”

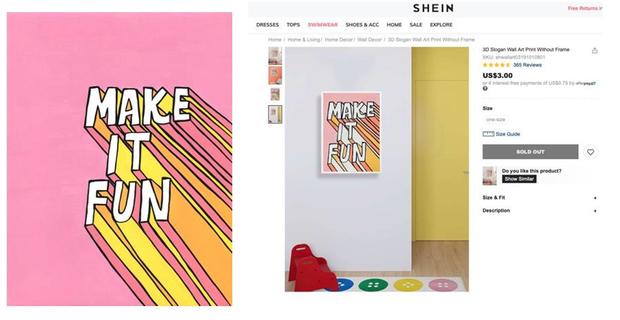

One of the designers who is suing Shein, Krista Perry of Worcester, Massachusetts, spotted copies of a graphic poster with the phrase “Make It Fun” for sale on Shein and a sibling site, Romwe.com. Perry protested to Shein via contact forms on its websites about the material, characterizing it as “incredibly disheartening, insulting and downright evil to profit off of artists without their knowledge or permission.”

Shein responded back with an offer of $500. “Shein made its offer as if it were a mom-and-pop operation rather than one of the richest enterprises in the world,” the suit argues.

Perry suffered “substantial damage to her business in the form of diversion of trade, loss of profits, and a diminishment in the value of her designs and art, her rights, and her reputation,” the lawsuit claimed.

The action argues that Shein’s pattern, when accused of copyright infringement, is to claim it had poor sales and blame a third-party organization for the theft.

“Shein will also offer an apology and a vague explanation that makes it seem that this was an anomaly — somehow Shein got its wires crossed and produced a very small number of exact copies of the designer’s goods,” the lawsuit states. “[N]ine times out of 10 the designer’s counsel will accept what’s offered, or bargain for just a little bit more.”

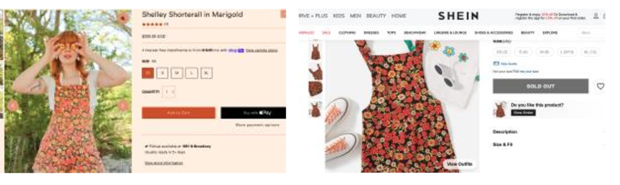

Two other designers, Jay Baron of Burbank, California, and Larissa Blintz of Los Angeles, also stated their designs were completely duplicated by Shein. Baron made artwork called “Trying My Best,” which was reportedly duplicated and sold by Shein, while Blintz’s “Orange Daisies” clothing was also allegedly copied.

Who owns Shein?

Part of the problem in pursuing Shein in court is its decentralized, even byzantine, structure, the lawsuit claimed.

Shein “is a loose and ever-changing (though still continuous even as some individual elements might change to be replaced by others) association-in-fact of entities and individuals,” the lawsuit alleged. Designers without an attorney “face an utter brick wall,” the lawsuit added, stressing that even people with lawyers by their side often struggle to find “an appropriate defendant.”

As a result, the claimants are charging a breach of the RICO Act, which is “designed to address the misconduct of culpable individual cogs in a larger enterprise,” the lawsuit claimed.

“Unrepresented parties face an utter brick wall,” the lawsuit argues. “But even plaintiffs with attorneys, with good cases, struggle to find an appropriate defendant. In the end, they simply sue any party they can locate, and try to straighten the situation out in discovery.”

Shein was launched in 2012 by Chinese entrepreneur Chris Xu, better known as Xu Yangtian, who is valued at more than $10 billion by Forbes. But not much is known about him, according to The Guardian, which noted the different reports about his background, with some stories describing him as a Chinese-American who studied at George Washington University, while others say he was born in Shandong in 1984 and studied at Qingdao University of Science and Technology.

“There is no Coco Chanel or Yves Saint Laurent behind the Shein enterprise. Rather, there is a mysterious tech prodigy, Xu Yangtian aka Chris Xu, about whom nearly nothing is known,” the lawsuit states.

What is a RICO charge?

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act of 1970 was established as a tool to counteract the exploitation of lawful enterprises by organized crime, according to the Justice Department. While commonly considered as a statute to combat organized crime, the RICO Act also has been used to prosecute white-collar crimes like the Enron accounting crisis and Bernie Madoff’s financial pyramid scheme.

Racketeering normally refers to a criminal conduct carried out by extortion or fraud, but the RICO Act also has a civil portion that can be utilized for consumer protection or to safeguard against commercial fraud, according to the Justice Department.

“It is well established that egregious copyright infringement (of the type alleged here, and of the type referenced in other similar cases against Shein) constitutes racketeering,” the lawsuit says.

A Congressional investigation last month unloaded a scorching condemnation of Shein and another Chinese shop, Temu.

The report is part of an ongoing Congressional investigation into products supplied to American consumers that potentially be created with forced labor in China. As part of the examination, the committee addressed letters in early May to companies Nike and Adidas, as well as Shein and Temu, asking for information about their compliance with the anti-forced labor statute.

Shein noted at the time that the company’s “policy is to comply with the customs and import laws of the countries in which we operate.” It also said it has “zero tolerance” for forced labor and has built a robust mechanism to verify compliance with U.S. law.